The Living Canvas: A Journey Through Italy's Renaissance Gardens

The Italian Renaissance, that extraordinary flowering of art, science, and human thought, did not confine its genius to canvases and cathedral domes. It spilled out into the open air, transforming the very landscape into a philosophical statement, a symbol of power, and a breathtaking work of art. To walk through a Renaissance garden is not merely to enjoy a pleasant green space; it is to step into a world where nature is persuaded to reveal a perfect, harmonious order. For the traveler seeking to understand this unique cultural achievement, Italy offers a living gallery of these designed landscapes, where the ideals of geometry, mythology, and humanism are etched into hillsides and sculpted from boxwood.

The journey into this world begins, fittingly, in the cradle of the Renaissance itself: Florence. Here, in the rolling hills just south of the city, lies the first and perhaps most iconic exemplar of the High Renaissance garden—the Gardens of the Villa Medici at Castello. Commissioned by Cosimo I de' Medici, this garden was a manifesto of Medici power and a reflection of the new Tuscan order. As you pass through the gate, the garden unfolds not as a wild, untamed nature, but as nature perfected. The central axis, a rigid spine of order, guides the eye and the foot. The masterpiece here is the Grotto of the Animals, a stunning grotta artificiale (artificial grotto) designed by Tribolo. Covered in multi-colored stones, shells, and mosaics, it houses lifelike sculptures of animals, once animated by hidden water jets that would surprise and delight visitors. It represents the Renaissance fascination with taming the wild—the cave, a symbol of primal chaos, is brought under human control and transformed into a theatrical spectacle. Castello sets the template: symmetry, axiality, water as a playful and symbolic element, and the seamless integration of sculpture and architecture with the planted environment.

A short distance away, the Boboli Gardens, stretching behind the immense Pitti Palace, represent the Renaissance garden evolving in scale and ambition. Where Castello is an intimate philosophical statement, Boboli is a grand theatrical set for the court of the Medici Grand Dukes. It feels less like a single garden and more like a series of outdoor rooms. The sprawling lawns, the steep amphitheater carved into the hill (which uses the palace as its backdrop), and the long, cypress-lined avenues speak of a power so immense it could reshape entire hillsides. The axis is no longer just a path but a grand promenade leading you upward to breathtaking panoramas of Florence, a deliberate reminder of who commanded this view. Key features like the Buontalenti Grotto, a Mannerist marvel of dripping stalactites and haunting figures like Giambologna's Venus Emerging from the Bath, push the Renaissance aesthetic into the realm of the fantastical and bizarre. Boboli demonstrates the garden’s transition from a private retreat for contemplation to a public display of absolute power.

To fully appreciate the Florentine innovation, one must venture north to the older, medieval heart of Italy. The Castello Estense in Ferrara offers a glimpse of a transitional form. The Duchess’s Garden, a recent and meticulous reconstruction, is a walled paradise of geometric perfection. Its raised beds, or parterres de broderie, are intricate patterns of low boxwood filled with colored gravel, resembling an embroidered carpet laid upon the earth. While it shares the Renaissance love for geometry, its mood is more intimate, more secretive, reflecting its pre-Renaissance origins. It is a beautiful precursor, a walled hortus conclusus (enclosed garden) that would soon have its walls conceptually broken down by the expansive vision of the Florentines.

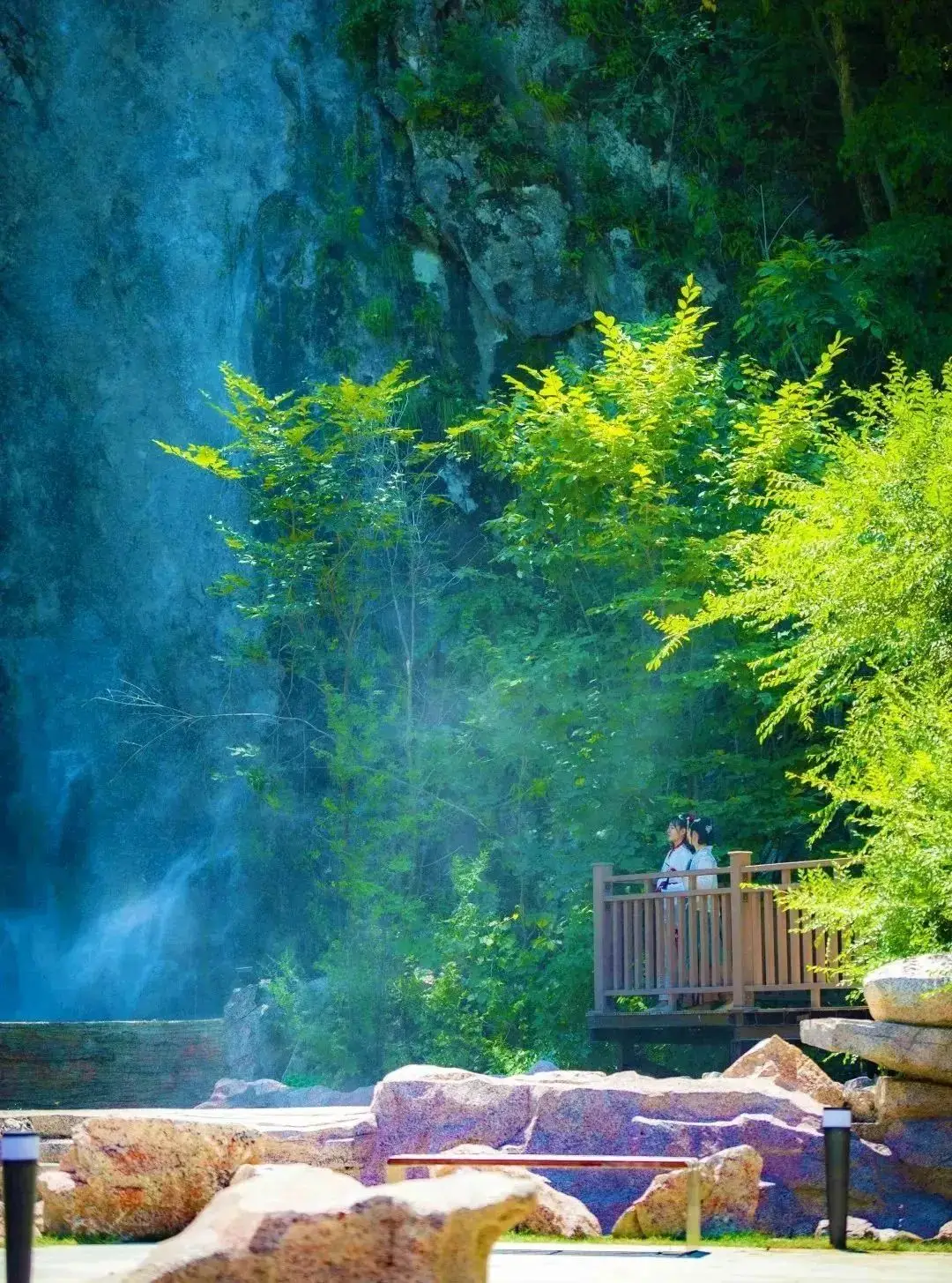

No tour of Renaissance gardens is complete without confronting the spectacularly bizarre and ingenious: the Sacro Bosco (Sacred Wood) of Bomarzo. Located in northern Lazio, this "Park of Monsters" is the antithesis of the rational, orderly Florentine model. Created by Prince Pier Francesco Orsini in the 16th century, it is a Mannerist garden designed to shock, confuse, and amaze. Here, you do not find serene axes and geometric beds. Instead, you wander through a wooded valley encountering colossal, surreal sculptures carved from the native rock: a giant tearing another in half, a monstrous elephant clutching a Roman soldier, a leaning house that disorients the senses, and a gaping mouth of an ogre inscribed with the words "All Reason Departs." Bomarzo is the Renaissance id unleashed. It reflects a world where certainty was beginning to crack, where artists and patrons explored the grotesque, the dreamlike, and the emotional. It is an essential counterpoint, proving that the Renaissance garden was not a monolithic style but a vibrant field for artistic experimentation.

Further south, near the eternal city, lies the Villa Lante in Bagnaia. If Bomarzo is a chaotic dream, Villa Lante is a harmonious poem, often considered the most perfect and refined example of the Italian Renaissance garden. Its genius lies in a single, unifying theme: water. The entire garden is a gradual, cascading descent of water from a mossy grotto at the top, down through a series of fountains, stone channels (catene d'acqua), and pools, finally culminating in a magnificent fountain in the lower parterre. The water tells a story of its journey from wild spring to civilized, controlled form. The twin casini (small palaces), built for two cardinal brothers, flank the central axis, emphasizing balance and partnership. The most enchanting features are the Water Chain, a stone chute where water rushes down creating a bubbly, textured surface, and the Cardinal's Table, a stone table with a central channel of flowing water to cool wine for outdoor banquets. Villa Lante represents the pinnacle of the Renaissance ideal—a perfect, self-contained world where art, nature, and intellect exist in sublime equilibrium.

Not to be outdone, Rome itself boasts spectacular examples, particularly the gardens of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli. Built by Cardinal Ippolito II d'Este, the son of Lucrezia Borgia, it is a monumental engineering and hydraulic marvel. The villa hangs on a steep hillside, and its entire design is a celebration of water power. Using a derivative of an ancient Roman aqueduct, the Cardinal created a symphony of fountains that is unsurpassed. The Avenue of the Hundred Fountains is a mesmerizing corridor where water spouts from countless masks into a long channel, accompanied by the sound of its endless murmur. The Oval Fountain is a grandiose, theatrical display, while the incredible Organ Fountain, a 16th-century hydraulic marvel, once used water pressure to play music automatically. The Villa d'Este is the Baroque spirit budding from the Renaissance root—it is about overwhelming the senses, demonstrating technological mastery, and creating a spectacle of sheer, awe-inspiring abundance.

From the philosophical order of Florence to the theatricality of Rome, Italy's Renaissance gardens offer a multi-layered journey. They are not simply beautiful places; they are complex texts written in the language of stone, water, and foliage. They speak of a time when humanity, newly confident in its place in the universe, sought to create its own perfect worlds on earth—worlds of reason, worlds of fantasy, and worlds of breathtaking beauty. To explore them is to understand a pivotal chapter in Western culture, not by reading about it in a book, but by living it, one serene path, one thundering fountain, and one surreal stone giant at a time.

发表评论